|

Winold Reiss: A Pioneer of Modern

American Design

C. Ford Peatross

This article originally

appeared in the publication "Cincinnati Union Terminal

and the Artistry of Winold Reiss," edited by Dottie Lewis

(Cincinnati, Ohio: The Cincinnati Historical Society, 1993).

It provides a general overview of Winold Reiss's work in architectural,

interior, and furniture design, or "stylings" as

he referred to many of his commissions. The author is currently

preparing a monograph on the subject of Reiss's designs, based

on recent research, to provide a considerably enlarged presentation

of this aspect of Reiss's professional career and to place

it in the context of comparable work of the period.

Cincinnati is especially fortunate in having

not only one of Winold Reiss's most ambitious commissions,

but also one of the few that survives, for the nature of most

of his work in commercial architecture and interior design

was necessarily ephemeral. As a public building, Cincinnati's

Union Terminal is also exceptional in Reiss's work, although

the many restaurants, hotels, and shops which he designed

were at one time a part of the daily lives of thousands of

people. So prolific was Reiss, that by 1940, not counting

the Cincinnati station, in any one day over 30,000 Americans

lived, met, ate, drank, or were entertained in a Reiss designed

interior. Today Cincinnatians are alone in this privilege.

"Masterpieces" of architecture, landscape, and interior

design too often lie outside the paths of ordinary people.

Historians of vernacular and commercial architecture are now

directing increasing attention to the transitory structures

which constitute such an important part of our built environment,

and which play significant roles in the quality of our lives.

Although most of his works as an architect and interior designer

have disappeared, during four decades of practice Winold Reiss

set a course that in considerable measure contributed to and

enlivened American design. This is an introduction to that

largely unrecognized journey.

| |

|

The Atlantic liner S. S. Imperator docked

in Hoboken, New Jersey, on October 29, 1913, bringing with

it from Hamburg three ambitious young men: Fritz Winold Reiss,

Oscar Wentz, and Alfons Baumgarten, each of whom played a

role in introducing modern design to the United States. One

was a young, brash, energetic, and talented artist fresh out

of Munich, then one of Europe's thriving art centers. Fritz

Winold Reiss (1886-1953) was well prepared to make his mark

in the New World. Trained by his father, the artist Fritz

Reiss, and at both the Royal Academy of Art, under the famous

painter and sculptor Franz von Stuck, and the Kunstgewerbeschule

(School of Applied Arts), under the equally notable poster

artist Julius Diez, he represented the coming together of

two great streams of artistic endeavor, the fine arts and

commercial art, which was a notable characteristic of his

time.

The professions of commercial and industrial design as we

know them today developed out of this stimulating convergence.

We are just beginning to study and to recognize the multiple

contributions which Reiss made to American architecture and

design. He helped to prepare the way for figures like Raymond

Loewy, Norman B. Geddes, Donald Deskey, and Walter Dorwin

Teague among others who established the United States as world

leader in commercial and industrial design during the 1930s.

In 1913, however, this country was on the distant edges of

the coming wave of change.

It is useful to observe that Reiss's education

in Munich's Kunstgewerbeschule reflected a turn-of-the-century

optimism that artistic talent and energy could and should

be productively channeled to the creation of the objects of

everyday life; that the lives and work of artists, artisans,

and workmen should be more connected; and that both commerce

and the human spirit would profit from such association. Riding

the crest of the Industrial Revolution, during the second

half of the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth

centuries, study and training in the applied arts were the

object of considerable attention in Great Britain, Europe,

and, finally, in the United States, where industrial design

ultimately emerged as an independent profession. The career

of Winold Reiss was congruent with the birth of that profession

from the seeds of the Arts and Crafts and Applied Arts movements.

But it was more. Reiss brought to his work not just the principles

and skills afforded by his excellent training, but his own

artistic talent, allowing him to create works whose energy

and imagination continue to speak to us today, bringing both

pleasure and inspiration. The decorative vocabulary of Vienna's

Secession movement, the bold colors and forms of German Expressionism,

and the conventions and abstractions of African art, all evident

in Reiss's early work, were to be transformed into something

distinctly American.

From across the Hudson River, Reiss and his

companions were greeted by the daring new skyscrapers of the

world's greatest city. Considerably less daring was New York's

attitude towards modern art, notably demonstrated several

months earlier in its reaction to the famous Armory Show.

American discomfort extended to the realm of commercial design

as well, as they were soon to discover. Undaunted, perhaps

even challenged by this unreceptive atmosphere, Reiss and

one of his fellow passengers, Oscar Wentz, set out almost

immediately to introduce the bold colors and daring forms

of Modern Decorative Art to the land of the Puritans.

Wentz possessed something that was completely at home on these

shores: a keen entrepreneurial spirit which spurred him to

develop a wide range of projects. The direct result was to

provide Reiss with an immediate stimulus and patronage for

his work, including graphic and interior design, launching

his career and advancing Wentz's.

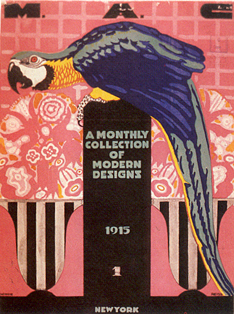

Oscar Wentz served as an avid propagandist and

promoter of modern commercial art. Within two years of his

arrival he founded the Society of Modern Art and began to

publish its official organ, the Modern Art Collector (M.A.C.)

(1915-18). Unprecedented in the quality and style of its printing,

as well as its subject matter, the M.A.C. served as

the main tool to promote the goals of the Society of Modern

Art and the work of its members. Wentz simultaneously attempted

to popularize the Art Poster Stamp in this country and enlisted

the support of executives in the infant motion picture industry

interested in improving American poster design.

He was described in 1929 as "a pioneer of modern art

in this country and the first president of the Society of

Modern Art, an early group of modem artists ."

Reiss played a key role in the production of

the early issues of the M.A.C., so much so that one

wonders when he had time to sleep or eat during its first

six months of publication. This work drew upon his experience

in creating the first issue of a periodical entitled Jungvolk

while still in Germany.

From September to December of 1915, he designed three of the

M.A.C.'s first four covers, much of what was inside, and

in large part established its graphic identity. Particularly

Reissian were the undulating vertical and horizontal lines

employed in borders and the slanting or falling letter "S,"

which later became hallmarks of his architectural and graphic

design projects. It is revealing to compare Reiss's first

M.A.C. cover to a poster designed in 1908 by Julius

Diez, his professor at Munich's Kunstgewerbeschule,

to promote an important applied arts exhibition.

Diez silhouettes a bold symbol of the genius of the arts applied

to the tools of industrial production against the outline

of Munich's Frauenkirche, while Reiss places a colorful parrot

and abstracted flower vases against a bright pink background

into which they partially blend. Both employ bold lettering

and simplified forms, large expanses of flat and contrasting

colors, and strong lines: the distinctive attributes of the

German Poster Style.

While the first M.A.C. cover was self-consciously

sophisticated and represented a tour-de-force of the lithographic

art, the tenth (ca. 1917) shows us another, quite different,

side of his artistic personality, the love of primitive natural

motifs and the ability to reduce and simplify them to essential

patterns of form, line, and color. The bird and flower motif

becomes a signature in much of Reiss's later work. The pages

of the M.A.C. also are useful in providing evidence

of the diversity and success of his beginnings. The start

of a long career as an educator is signaled by a witty promotion

for the Winold Reiss School in which an artistic cherub armed

with a dripping brush tames a bucking tube of tempera. A more

restrained presentation of the importance of good lettering

in advertising was clearly designed to appeal to a different

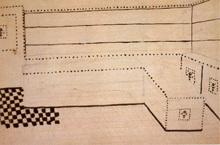

audience of conservative businessmen. Reiss's first architectural

commission, the Busy Lady Bakery of 1915 (described in 1939

as the first modern store in New York) is covered at length.

Emphasis is given to the involvement of the artist in every

aspect of the store's design, from its interior and exterior

architecture to its advertising and bold blue and white packaging,

all illustrated in the M.A.C. Reiss worked out the

spare but elegant essentials of the interior design scheme

for the Busy Lady in a small design sketch whose strong lines,

squarish grids, and punctuation of broad flat surfaces with

simplified decorations recall the work of Josef Hoffmann and

the Vienna Secession and at the same time establish a recurring

theme in his own work.

The look of the M.A.C. was dramatic,

bold, colorful, self-consciously modern, and German. This

augured both good and ill for the fate of the publication,

for Germany, and Munich in particular, led the world in printing

technology and graphic design. The pages of the M.A.C.

are filled with the advertisements of printing firms and suppliers

throughout the United States with German origins: the Stockinger,

A. Bielenberg, and Zeese-Wilkinson Companies of New York;

Berger and Wirth of Brooklyn; Charles Hellmuth of New York

and Chicago; the Manternach Engraving Company of Hartford;

F. Weber & Co. of Philadelphia; the Meinzinger Studios

in Detroit; Frank B. Nuderscher of St. Louis; and the Barnhart

Brothers of Chicago, St. Louis, Washington, Dallas, Omaha,

Kansas City, Saint Paul, and Seattle, among others. Chicago's

Society of Poster Art styled itself as specializing in the

"Munich System" of designing and printing. None

of this commercial goodwill, however, was to prove equal to

the rising tide of anti-German feeling related to the First

World War (1914-1918), which the United States entered in

its last year. Modern German art had no place in a nation

whose army grew from 160,000 to 3,500,000 between 1916 and

1918 and was rationing meat and sugar in order to stop another

sort of Teutonic offensive.

The final issue of the M.A.C., published in 1918, put

forward its brand of Modern Art as European rather than heavily

German, and promoted the third Liberty Loan and the patriotic

involvement of all artists, but it was to prove too little,

too late.

| |

|

|

|

Reiss worked out the spare but elegant

essentials of the interior design scheme for the Busy

Lady in a small design sketch with strong lines, squarish

grids, and punctuation of broad flat surfaces with simplified

decorations. |

To return to the last of our Atlantic voyagers,

Alfons L. Baumgarten was important primarily for providing

Reiss with an introduction to his brother, Otto, already well

on his way to becoming one of New York's leading restauranteurs.

Within a decade after his arrival in New York, Otto J. Baumgarten

came to preside over a small empire of the city's finest restaurants,

including the Voisin, the Crillon, the Esplanade, and the

Elysée.

Initially trained at his father's restaurant in Vienna, the

hearth of the modern movement in architecture, Baumgarten

was not blind to the commercial advantages of good design,

and saw the wisdom of using his eating establishments as a

proving ground for Reiss's work in interior decoration, for

which they provided a highly visible and suitable stage. The

first Restaurant Crillon of 1919-20, located at 15 East 48th

Street, caused a sensation referred to repeatedly over the

next two decades.

Called the "first modernistic interior in America,"

it featured flat, starkly delineated wall surfaces; prismatic

hues; and large, simplified decorations, presaging the "super-graphics"

of our own time.

All are evident in one of Reiss's small design sketches, where

the bird-and-flower theme of the decorative wall panels recall

the second cover of the M.A.C., and the avant-garde

furnishings are right out of Vienna. Another Baumgarten enterprise,

the manufacture of chocolates, led to the creation of establishments

such as the Baumgarten Café Viennois and Baumgarten

Viennese Bonbonnière, for which, in addition to architecture,

Reiss designed packaging and even the delivery truck,

continuing a pattern begun with the Busy Lady Bakery and extending

throughout his career.

Otto Baumgarten also collaborated with Reiss as a consultant

in restaurant management, bringing his expertise to many other

American restaurant projects."

|

|

Reiss's first architectural commission, the Busy Lady

Bakery of 1915 (described in 1939 as the first modern

store in New York) is covered at length. The artist

was involved in every aspect of the store's design.

He designed its interior and exterior architecture,

as well as its advertising and bold blue and white packaging.

|

Wentz's M.A.C. and Baumgarten's Crillon

commissions were key factors in the first decade of Reiss's

design career in America, paving the way for increasing success

during the 1920s, out of which he emerged as a well-known

figure in American interior decoration and textile and furniture

design. It was a decade framed by design commissions for two

important hotels, the Alamac and the St. George.

Harry Latz, the developer of the Hotel Alamac,

gave Reiss considerable artistic and financial freedom in

its decorating scheme, to notable effect.

The public rooms of the building were conceived in two very

different styles. In her 1925 article for the International

Studio, the critic Margaret Breuning wrote: "One

realizes the emphasis of decoration in modern murals in the

work of Winold Reiss, who has done a number of restaurants

and most recently the Alamac Hotel. The Hotel Alamac has many

motifs in its decorations varying with the intended use of

the rooms as well as their shape and size. The mediaeval room

is one of the most effective. Its panels represent picturesque

figures of the Middle Ages. The huntsman, the lady fair and

the valiant knight alternating with rich metal panels elaborately

carved. The Congo Room, also known as Congo Roof or Congo

Grille, makes use of the motifs of primitive African sculpture

and ornament, not only in its murals but also in its furnishings

down to the most trivial detail. The effect is remarkably

impressive."

Writing almost a decade later about the use of decorative

metalwork in Rockefeller Center, Eugene Clute identified Reiss's

work at the Alamac as the first and best of its type: "Perhaps

the first notable example of this kind of metal work was the

series of large decorative wall panels that were designed

by Winold Reiss for the Hotel Alamac, New York City, and installed

in the grill room when that hotel was built, ten years or

more ago. They were executed in a combination of metals worked

in repoussé, including wrought iron, copper, brass,

steel and aluminum. The craftsmanship was executed by Julius

Ormos and Charles Bardosy. The work represented scenes of

the chase, rendered with an admirable sense of decorative

values and a feeling for the technique employed."

The Architect and Building News compared the decorative

metal panels with the work of Edgar Brandt, one of the leading

artists of the period.

|

The Crillon Restaurant, called the "first modernistic

interior in America," featured flat, starkly delineated

wall surfaces; prismatic hues; and large, simplified

decorations, presaging the "super-graphics"

of our own time. All are evident in one of Reiss's small

design sketches.

|

Far removed in both style and distance from

its medieval grill room was the Alamac's daringly conceived

Congo Roof, which represented Reiss's and New York's first

treatment of a tropical theme. Drawing on his knowledge of

both Cubism and African Art, the commission allowed Reiss

to begin to develop a decorative vocabulary that became a

key part of his own repertoire and has remained a popular

sub-theme of American restaurants and nightclub decoration

to the present day. Its stylistically advanced, Cubist-related

ideas are described in New York 1930: "The Congo

Room was part of a rooftop restaurant known as the South African

Garden that, according to Architecture and Building,

was destined to appeal to those craving 'an unusual and garish

setting for their meals.' Elevators whisked diners to a rooftop

entrance vestibule with grass flooring and a straw-covered

ceiling. Entered through the jaws of a vividly painted mask,

the restaurant itself resembled an African village. The theme

was carried out in the chairs and tables and the murals of

leopards, chimpanzees, and snakes. Diners seeking privacy

could take their meals seated at booths made to resemble thatched

huts, which lined the walls and focused on a native 'council

chamber' from which an orchestra blared its jazz. Each chair

back simulated a tribal mask, and the general lighting emanated

from idol masks suspended from the ceilings."

| |

The decoration of the Alamac's rooms,

suites and corridors were also a part of Reiss's commission,

and they allowed him to draw upon the principles of Modern

Decorative Art as they applied to residential interiors.

In a sketch for a sitting room in one of the hotel's suites

(top) we can see its similarities to a domestic interior

(bottom) published in the first issue of the M.A.C. |

| |

|

| |

|

The decoration of the Alamac's rooms, suites,

and corridors was also a part of Reiss's commission, which

allowed him to draw upon the principles of Modern Decorative

Art as they applied to residential interiors. In a sketch

for a sitting room in one of the hotel's suites we can see

its similarities to a domestic interior published in the first

issue of the M.A.C., part of a feature on the work

of E. H. and G. G. Aschermann, a Viennese team designing American

interiors in the spirit of the Wiener Werkstätten. Mr.

Aschermann was described as having studied with Josef Hoffmann,

and nothing shown belies this. The simple lines of the furniture

are emphasized by their black finish, echoing the strong outlines

of the baseboard, carpet, french doors, and window. Wall panels

bordered in brilliant blue with bright yellow accents complete

the ensemble. Both the Aschermanns' and Reiss's interiors

were unprecedented in American residential architecture of

the period, and would have appeared strikingly modern in the

1930s, as they do, indeed, today. Whereas the Aschermanns'

design was advanced, Reiss's interior was more daring and

original in the studied informality of its furniture arrangement,

the use of brilliantly colored accessories to accent an abstract

painting over the mantel, and simplified graphic elements

punctuating the door and wall planes. All of these potentially

jarring and clearly stimulating elements are harmoniously

combined to create a unified effect. Both designers embody

precisely the characteristics of modern German decoration

observed by French designers between 1908 and 1910 and used

to define and create their own unique and modem style.

Reiss's work in residential interiors during

the 1920s ranged from hotels and apartment buildings to individual

apartments and furniture and fabrics for the domestic market.

Much of it was highly experimental and innovative in character

— including the use of many new materials: in metal,

aluminum and chromium; in fabrics, synthetic products such

as rayon and Du Pont's Fabrikoid and Nemoursa; and paints

and wall coverings like Duco and Muralart, an early type of

Formica. The new types of finishes, effects (including air-brushing),

and colors that these materials allowed were further extended

by the use of new lighting techniques and fixtures. In addition

to working as a color consultant for Du Pont's Fabrikoid and

Muralart product lines, during this period Reiss designed

new products for many companies: fabrics for Mallinson, Schumacher,

Mosse, Martex, and Shelton Looms; furniture for Thonet and

General Fireproofing; lighting fixtures for Egli; and packaging

and advertising for a wide range of clients. His work was

featured in various exhibitions sponsored by New York's leading

department stores as well as the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In 1928 he joined a number of leading designers in forming

their own design showcase, the American Designers Gallery,

whose first exhibition was organized by Ely Jacques Kahn and

Joseph Urban. Reiss, Paul Frankl, and Donald Deskey were credited

with presenting the designs most likely to make "a practical

contribution to an evolving Modernism."

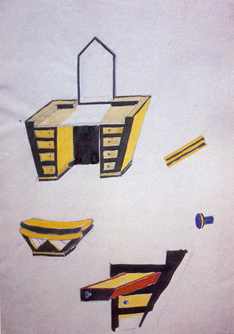

A few examples illustrate a less practical

but equally sophisticated aspect of Reiss's work in these

areas, the distinctive brand of "zig-zag" modernism

that he evolved during the 1920s, drawing inspiration from

native American motifs.

Although a boyhood fascination with native Americans drew

him to this country, the artist's first western trip, including

Montana, Colorado, New Mexico, and Mexico, did not take place

until 1920, followed by a second and longer stay in Montana

in 1927.

Reiss's academic training in the use of pattern and color

made him highly receptive to native American motifs, which

increasingly found their way into his graphic and commercial

design work. The use of either a zig-zag line (chevron) or

row of linked triangles, commonly used in the art of the Blackfoot

and Sioux nations, became a signature of Reiss's work from

the late 1920s onward.

American, European, and modern sources all come together in

the jagged composition of angles and bright colors that characterized

his 1928 design for the elevator cab of the Seelig and Finkelstein's

Shellball Apartments.

Although its interior no doubt rendered vertical travel more

stimulating than most residents of the building ever desired,

the design would have made any one of Prague's Cubist architects

proud. Sketches of metalwork designs, also related to the

Shellball Apartments, demonstrate Reiss's continuing experiments

in the decorative uses of metalwork and the effects of combining

different metals in a single composition. His eager quest

to introduce lively colors and imaginative ideas into American

furniture design is represented by a sketch for a dressing-table

and bench of complex angles and contrasting shades of bright

yellow, red, blue, and black, which echo the vocabulary of

the De Stijl movement and challenge any preconceptions concerning

their form.

| |

|

| |

His eager quest to introduce lively

colors and imaginative ideas into American furniture

design is represented by a sketch for a dressing-table

and bench of complex angles and contrasting shades of

bright yellow, red, blue, and black.

|

The 1920s also marked Reiss's first commissions

outside of the New York area, significantly in the great midwestern

metropolis of Chicago. Holabird and Root, one of that city's

most progressive architectural firms, was linked to three

of these, beginning with murals for the Apollo Theatre (1922-23)

and ending with the Walden Bookshop in the Michigan Square

Building (1930). Reiss's 1928 interiors for one of Chicago's

leading clubs, the Tavern, which occupied the twenty-fifth

floor of a Holabird and Root skyscraper at 333 N. Michigan

Avenue, were widely praised and publicized, winning him a

whole new list of admirers and clients from many parts of

the country.A contemporary article in The Chicagoan described

his achievement in glowing terms: "Winold Reiss, a leader

in the profession of interior decoration, was given the commission.

He was also given carte blanche, with John Root, of

the building committee, exercising the power of veto over

the designs as they were submitted. The result speaks for

itself. The rooms of The Tavern are the most brilliant example

of modern decorative style in the country. There is gayety

and originality, without eccentric affectation, in every detail.

The Tavern, in its physical aspect, is a work of art. And

being modern art, it has a dynamic quality; it refreshes and

stimulates. The visitor to this Tavern drops down to the street

and to everyday life, a better workman, at whatever craft

he practices, than he was before, because the colors and forms

of these rooms have put a new beat into his pulse and a new

vibrancy into his nerves.

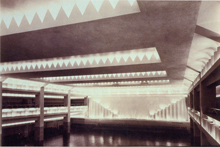

In 1930 Reiss completed extensive designs for

the vast interiors of Brooklyn's Hotel St. George, which,

with the addition of a thirty-one-story tower by architect

Emery Roth, became the nation's second largest. As many as

3,500 guests could occupy its 2,632 rooms, and its many dining

facilities were capable of serving up to 9,000 patrons at

any one time. Winold Reiss Studios conceived and designed

most of the public spaces in the new Tower Building, which

"included the largest indoor swimming pool in the metropolis

and the most expensive one ever built; the largest and most

costly banquet facilities in the world, embracing sixteen

magnificent rooms; the largest hotel ballroom in the world."

The architect and historian Robert A. M. Stern has sung the

praises of its ballroom, designed to hold over 3,000 people,

in the prose style of Tom Wolfe: "the single most startling

interior public space of the time in New York ... as completed,

with its myriad colored lights articulating every facet, the

ballroom was a brilliant tour-de-force, a real life version

of movie-modern, a last blaring wail of jazz-age stylishness

at its very best.

His old friend Oscar Wentz described Reiss's stylish treatment

of the entrance to the ballroom: "Leading to this room

is a huge foyer, the feeling of space in a measure imparted

by the 'scaping' (Reiss's terminology for his use of an abstract

decorative motif on floors, walls and ceilings) of the carpet

in three tones of red with diagonal lines suggesting broad

vistas. This same treatment is reflected in the cream ceiling

with bands of red and gold. Indirect light is softly diffused

from the ceiling and columns, casting its warm glow on the

gold and vermilion Muralart walls ornamented at intervals

with metal grill work.

The St. George constituted a city within a city, a great public

arena rivaled only by Cincinnati's Union Terminal among Reiss's

works.

| |

|

| |

Winold Reiss Studios conceived and

designed most of the public spaces in the new Tower Building

including the largest ballroom in the world which was

designed to hold over 3,000 people. |

| |

|

| |

Otto Wentz described Reiss's stylish

treatment of the entrance to the ballroom: "Leading

to this room is a huge foyer, the feeling of space in

a measure imparted by the 'scaping' of the carpet in three

tones of red with diagonal lines suggesting broad vistas." |

The great building boom of the 1920s, which

had provided Reiss with so many design opportunities and commissions,

came to an abrupt halt with the onset of the Depression. During

the 1930s Reiss's work was more restricted in range and harder

to find. Among his papers is a portfolio containing dozens

of elegant designs proposed to the Barricini candy company,

which Tjark Reiss says represent his father's attempts to

obtain commissions during this period. His prospects improved

following the repeal of Prohibition in December, 1933,

and a series of commissions from Henry Lustig for his Longchamps

restaurants provided Reiss's career with renewed stimulus

and visibility after 1935.

In addition to their famous culinary offerings,

the second generation of Longchamps restaurants enjoyed some

of New York's best locations and represented the height of

stylishness: "Longchamps is not naive; its is daring

and sumptuous," declared the critic Talbot Hamlin in

1939.

Lavish features introduced by the Longchamps chain included

the extensive use of mirrored wall surfaces and indirect lighting,

complex floor and ceiling levels, table telephone and twenty-four-hour

service, and receding plate glass windows that turned the

restaurants into outdoor cafes in good weather. The first

(1935) occupied the ground-floor corner of the Chanin Building

diagonally across from the Chrysler Building, with lobby entrances

from both 42nd Street and Lexington Avenue, while the largest

and most successful (1938) was ingeniously arranged on five

levels of that icon of American architecture, the Empire State

Building.

The exterior of Reiss's 1941 design proposal

for a new bar and roof garden at the 49th Street and Madison

Avenue Longchamps displays the chain's trademark vermillion

coloring and lettering, including the falling "S,"

while the undulating lines that enliven its canopy and bronze

wall panels recall the early borders of the M.A.C. The

entire effect is not dissimilar to that of the Barricini candy

box already illustrated: the name or sign identifying the

product or establishment has been completely integrated into

its design; the façade has become a sign rather than

simply providing a place for one.

The care given to the smallest details in the

Longchamps projects, as well as a willingness to experiment

with the decorative possibilities of new materials, is demonstrated

in a design sketch for the inlaid formica top of a bar table.

A Longchamps lobby card of the period is a brilliant exercise

in graphic design,

exhibiting the same qualities. It announces "Cocktail

Time" in a colorful and inviting display with lettering

punctuated by the same motif of linked triangles that Reiss

had used to architectural effect in the ballroom of the Hotel

St. George. The bold treatment of the interiors of the Longchamps

can be observed in a 1946 sketch for the new retail shops

of the 57th Street branch.

Reiss visibly moves the patron through a gauntlet of shop

windows by means of an undulating floor pattern and rhythmic

frieze in which he returns to his roots for inspiration, employing

motifs almost identical to those introduced a half-century

earlier by Kolomon Moser, the great Viennese Secession designer,

in his own house.

The success of Lustig's and Reiss's collaboration has been

summed up in this way: "The Longchamps restaurants brought

to a middle-class audience the glittery glamor of such highly

exclusive haunts of New York's cafe society as the Stork Club

and El Morocco ... [and] represented the culmination of a

decade's search for an opulent and even playful modern language

of form."

| |

|

| |

The exterior of Reiss's 1941 proposal

for a new bar and roof garden at the 49th Street and

Madison Avenue Longchamps displays the chain's trademark

vermillion coloring and lettering, including the falling

'S', while the undulating lines which enliven its canopy

and bronze wall panels recall the early borders of the

M.A.C.

|

Following Lustig's sale of the restaurants in

1946, commissions followed for three more Longchamps, completed

between 1950 and 1952. The first, in New York's Manhattan

House, employed Reiss's lifelong mastery of tropical themes

to good effect; another, in Washington, D.C., featured native

American murals and decorations; and the last and least, in

Philadelphia, was carried out in a watered-down Colonial style

that clearly indicates a reduction in Reiss's activity following

a stroke in 1951. Taken as a whole, the Longchamps commissions

played a critical role for Reiss, providing him with new design

opportunities and placing his work squarely in the public

eye. During the last two decades of his career, the Longchamps

work led to many other new commissions, large and small, for

the "stylings" of restaurants, hotels, and commercial

establishments in many parts of the country.

By the mid-1940s at least six Reiss-designed

establishments, including the Steuben Tavern, the famous Lindy's

Restaurant, and four of the nine Longchamps, were within walking

distance from Times Square and New York's Theater district.

The average Longchamps was capable of serving some 800 patrons

at a time, while one employed fifty bartenders. Beginning

with the Crillon of 1919-20, for three decades anyone dining

well in the world's greatest metropolis, including thousands

of visitors, would have been familiar with, if not aware of,

Reiss's designs. This was also true to a lesser degree in

Chicago, with Reiss interiors at the Tavern Club, the Palmer

House, and the Sherman Hotel; in Los Angeles, at Mike Lyman's;

and at restaurants in cities such as Holyoke, Massachusetts,

and Allentown, Pennsylvania.

|

|

|

A willingness to experiment with the

decorative possibilities of new materials, is demonstrated

in a design sketch for the inlaid formica top of a bar

table.

|

|

In 1949 Reiss received a commission for Montreal's

Chic-N-Coop Restaurant, conceived, in spite of its name, very

much in the elegant spirit of his Longchamps works.

At the age of sixty-four he proved himself to be as creative

and imaginative as ever, producing stacks of sketches and

drawings in many variant schemes for its exterior, interiors,

and graphic identity.

This brief overview is not the place to attempt

any final evaluation of of Reiss's contributions to American

design but has tried to bring some of them to more general

attention. His introduction of entirely new uses and types

of color; experimentation with new forms and materials; incorporation

of poster-like graphic elements; and integration of native

American decorative motifs represent some of the most promising

areas for further study and analysis. It is appropriate to

close with a recent statement by the architect Morris Lapidus,

whose own work is currently the object of renewed appreciation.

His credentials include the practice of architecture in New

York City from 1927 until the early 1960s, providing him a

thirty-year perspective of developments in American design.

Earlier this year, following his return from a lecture at

Yale's School of Architecture, I asked Lapidus if he remembered

Reiss's work and if it had had any effect on his own.

Without hesitation, he admitted instances of his influence

and recalled that, as the preceding pages have attempted to

show, "Reiss was way ahead of all of us."

| |

|

| The bold treatment of the interiors

of the Longchamps can be observed in a 1946 sketch for

the new retail shops of the 57th Street branch. |

| |

| |

|

| |

Between 1950 and 1952 Reiss designed

three more Longchamps, the first in New York's Manhattan

House.

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

The Manhattan House design employed

Reiss's life-long mastery of tropical themes.

|

| |

| |

| |

|

| |

At the age of sixty-four he proved

himself to be as creative and imaginative as ever, producing

stacks of sketches and drawings in many variant schemes

for the exterior, graphic identity, and interiors of Chic-N-Coop

in Montreal. |

| |

|

Endnotes

Winold

Reiss came to be much better known for his work as a portraitist

and muralist. This has been partly responsible for obscuring

his reputation as a commercial artist, to which this analysis

attempts to provide a brief introduction. The stigma that

continued to attach itself to commercial art work in this

country often threatened and sometimes compromised the artist's

noncommercial career. Reiss's work as a painter and muralist,

together with the training and theory of artistic practice

that supported it, should not be viewed as a separate but

rather as an integral aspect of his work in architecture and

design. A superb education in one of Europe's most progressive

artistic centers instilled in the young artist a firm and

life-long belief in the unity and equality of the arts of

design, and made of him a stalwart soldier in the battle to

bring the talents of artists to the service of a wider range

of design problems. The Winold Reiss who disembarked from

the S.S. Imperator carried with him to America a willingness

to devote as much energy and ability to the design of posters,

magazine covers, advertisements, fabrics, floor coverings,

wallpaper, textiles, furniture, and interiors as to easel

paintings or mural decorations. His work in these areas ultimately

may prove to have been more influential than his more traditional

artistic endeavors. Tjark and Renate Reiss have been unfailing

in their hospitality, encouragement, and support in regard

to my interest in Reiss's design career and have been very

generous in helping to establish a representative collection

of his work in the Prints and Photographs Division of the

Library of Congress. Tjark Reiss, in particular, shares my

opinion that his father's contributions in this area have

yet to be suitably recognized. This effort may serve, in some

small measure, to correct this situation. While periodic access

to Reiss's archives since 1987 has allowed me certain insights

into his career as a designer, this can only supplement the

years of careful and painstaking documentary investigations

represented in Fred Brauen, "Winold Reiss (1886-1953):

Color and Design in the New American Art," (New York,

1980), an indispensable tool for anyone attempting a study

of this subject. Back.

The

cause of Modern Decorative Art is cited repeatedly

in the manifestos published by Reiss and Wentz in the M.A.C.

and elsewhere during the next two decades. See "A Word

About Modern Decorative Art," M.A.C., vol. 1,

no. I (September 1915): At no time has Decorative Art been

so much the subject of discussion as at the present. There

are two reasons for this. First, by the revival in Europe,

especially in the German-speaking countries, of decorative

art, i.e., of Art in its applied forms. Second, by the misinterpretation

of the words "Decorative Art" as used in the modem

sense of the word and the misunderstandings arising therefrom

.... Modern artists wittingly or unwittingly have changed

the meaning of the words "Decorative Art." In their

meaning of Decorative Art they seek to express in a form,

or series of forms, a certain feeling—this feeling they

call "decorative". The feeling expresses itself

through strong lines and broad colors. Sometimes the colors

are very bold, even crude and hard in combination. Sometimes

they are soft and harmonious, but always the same quality

runs through all; the general effect is big, broad, and simple.

The bigger and simpler the effect, the more decorative the

work. Back.

See

Robert E. Irwin, "Posters and Motion Pictures,"

Modern Art Collector (M.A.C.), vol. 1, no. 2 (October

1915). Irwin was an executive in the Poster Division of Metro

Pictures Corporation. Back.

The

New Tork Times Magazine, March 10, 1929, p. 14. Back.

Tjark and Renate Reiss possess a copy

of this rare amateur publication, whose cover, borders, and

illustrations were designed by Winold Reiss in a manner inspired

more by the Jugendstil and the work of Charles Rennie Mackintosh

than the later Munich School. Reiss also contributed a number

of poems to Jungvolk which demonstrate his romantic

sensibilities. Back.

Friedrich Achleitner, Österreichische Architektur

im 20. Jahrhundert, Ein Führer in drei Bänden,

vol. 3, pt. I (Vienna: Museum für Moderne Kunst, 1990):

93-94, illustrates comparable distinctive undulating bands

employed by the architect Otto Wagner to decorate the exterior

of Vienna's Leopoldstadt railway station, ca. 1904-1908, showing

the motif as a part of the contemporary design vocabulary.

Reiss never visited Vienna, but he employed this motif to

decorate the interiors and exteriors of many of his own buildings,

sometimes in mosaic, as in the façade of the Restaurant

Longchamps at 59th and Madison Avenue of 1939. Back.

This was perhaps adopted either from the work of his colleague

Ilonka Karasz or from Frank Nuderscher, who both employed

the motif in early issues of the M.A.C. Back.

Ulrich Thieme and Felix Becker, eds., Allgemeines Lexikon

der Bildenden Künstler von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart,

vol. 9 (Leipzig, 1978), pp. 280-281. Known not only for

his posters, Diez provided illustrations for the famous publication

Jugend and designed book covers, bookplates, and advertising

art, as well as mural decorations and mosaics for the new

buildings of the University of Munich, the Wiesbaden Kurhaus,

the Nürnberg train station, and other public buildings.

Back.

"A Word About Modern Decorative Art," M.A.C.,

vol. 1, no. I (September 1915), offers the following description,

referring to examples which the publication intends to illustrate:

"Whether a subject is treated with the large expanses

of flat color technique, generally known as the German Poster

style, or with much detailed work, matters not. What matters,

is the broad and simple feeling which finds its expression

in the general effect. If there are many details, they must

be subordinated to the effect in such a way that they do not

weaken or disturb it." In a subsequent article in the

same issue, "Modern Decorative Art for the Advertiser,"

by Raymond Cavanaugh, the author insists that "the claims

of Modern Decorative Art for commercial recognition must be

given the fullest consideration," exhorting the reader

with the confidence of the newly converted: "Let him

[the advertiser] turn to a poster of today, executed in the

true spirit of Modern Decorative Art, and he will find positive

virtues only. There are no negative qualities in Modem Decorative

Art. To put it slangily, it has the 'punch'. Its color is

a joy. Its composition is impressive; its general impression

one of strength, force and character."

Back.

L. 0. Duncan, "The Belle of Yesterday," The Store

of Greater New York (August 1939): "Her lines are

no longer modish, although when she was opened to public view

in 1915, she was the first modern store in America. A great

howl went up from the designers of that period. They sneered

and said that she was too extreme, almost decadent. Sneerers

told architect Winold Reiss to take her back to Paris."

Back.

R. R. Palmer and Joel Colton, A History of the Modern World

(New York 1965), p. 686.

Back.

Brauen "Winold Reiss," p. 17, reports that Otto

Baumgarten reached New York in 1908, after working in Paris

and London, rising through the ranks to become commis at the

Plaza before opening the Restaurant Voisin in 1913.

Back.

Brauen, "Winold Reiss," pp. 18, 21, 25-26, has painstakingly

traced many of these references. See also Robert A. M. Stern,

Gregory Gilmartin, and Thomas Mellins, New York 1930: Architecture

and Urbanism betweeen the Two World Wars (New York, 1987),

pp. 283-84: In 1920 Reiss had pioneered a less scenographic

restaurant design in New York at the Crillon Restaurant at

15 East Forty-eighth Street, which he decorated in what Edwin

Avery Park described seven years later as a "decidedly

modern and thoroughly American taste, using flat surfaces,

broad and colorful painted decoration, based on the patterns

found in Navajo blankets and Indian pottery."

Back.

Brauen,

"Winold Reiss," p. 25, cites both Beverly Smith

in the American Magazine 113 (January 1932), pp. 26-27,

describing the initial Crillon as "the first really modernistic

interior in America, which made a great stir and won him [Reiss]

other important commissions," and Margaret Breuning,

"Tendencies in mural decorations," International

Studio 82 (December 1925), p. 177-178: "About six years

ago Mr. Reiss decorated the Crillon Restaurant and created

quite a flutter in the dovecots by his colorful work. Among

other features of this building was a room treated in modernistic

style and prismatic hues."Back.

Brauen, "Winold Reiss," p. 83, n. 40.

Back.

"Let the Motif be Modern, Advises Expert,"

An Interview with Winold Reiss, The Restaurant Man

(April, 1931), 14: "When Mr. Reiss is called in to design

a restaurant, he usually also designs the furniture and even

the menu cards and meal check, for he believes that all of

these combinations are instrumental in expressing the character

of the establishment." Back.

"Let the Motif be Modern, Advises Expert,"

An Interview with Winold Reiss, The Restaurant Man

(April 1931), 15: "The Crillon's owner, Mr. Baumgartner

[sic], incidentally, is a partner of Mr. Reiss in the restaurant

decorating division of the latter's studios. An unusually

effective combination they make—Mr. Reiss the artist

and decorator and Mr. Baumgartner being a successful restauranteur."

"Winold Reiss Co. Doing Decorations for Alamac,"

The Restauranteur (August 11, 1923), p. 8, stated that

the upper Broadway building, nearing completion, was decorated

by "the Winold Reiss Decorating Company, of which Otto

J. Baumgarten, the noted restauranteur, is the business manager."

Baumgarten was identified as a partner as well as business

manager of the Reiss firm, and as the "proprietor of

the famous Crillon Restaurant ... one of the most beautiful

examples of decorating to be found anywhere .... When it is

taken into consideration that Mr. Baumgarten is an experienced

hotel and restaurant man who thoroughly understands this business,

his position as general business manager for the Winold Reiss

Decorating Company makes this company especially fitted to

handle satisfactorily all hotel and restaurant work."

Back.

"Winold Reiss Co. Doing Decorations for Alamac,"

The Restauranteur (August 11, 1923), p. 8, identified

Latz as a developer who "has made up his mind at the

start that he would spare no expense in making the new Alamac

the very finest possible, and he has shown his excellent taste

by selecting Mr. Reiss for this important commission."

Back.

Margaret Breuning, "Tendencies in mural decorations,"

International Studio 82 (December 1925), pp. 177-178.

Back.

Eugene Clute, "Today's Craftsmanship in Combining Metals,"

Architecture (October 1934), pp. 203-205.

Back.

"A Modern Decorator

in New York," Architect and Building News (November

26, 1926), p. 634. Back.

Stern,

New York 1930, p.283. Back.

Yvonne Brunhammer and Suzanne Tise, The Decorative Arts

in France: La Société des artistes décorateurs,

1900-1942 (New York, 1990): 26: "A dramatic change

in the style of the works exhibited in the salons of the Société

came about as the result of a second manifestation of the

Munich Werkstätten—their appearance in Paris at

the Salon d'Automne in 1910. Since 1900 the growing artistic

and commercial success of the Werkstätten had been a

cause for alarm in France. There was even more concern after

an important applied arts exhibition in Munich in 1908, when

the French delegation, which included one of the founders

of the Société des artistes décorateurs,

Rupert Carabin, returned to report that the German exhibition

represented for France an "artistic and commercial Sedan."

The delegation later reported to a conference on the decorative

arts in Nancy that the long-sought-after modern style had

not been born in France, but in Germany: "The ruling

principle that inspires the young German school is to create

harmonious ensembles through a collaboration of sculpture,

painting and architecture, and the group has endeavoured to

realize this by reforming the aesthetics of the home to make

the modern house a combined work of art, a practical construction

of simple and dignified beauty ... Thanks to the simplicity

which they intentionally seek, they have succeeded in creating

furniture designs of good quality and irreproachable form

that may be executed entirely by machine, so that they are

within the reach of modest budgets. It was after the delegation

returned from Munich in 1908 that Frantz Jourdain ... invited

the Munich Werkstätten to exhibit in Paris in 1910....

When the Salon opened in October, the Munich group... filled

eighteen rooms with the finest products of modern German decorative

artists organized on the theme of the 'House of an Art Lover'...the

interiors were not particularly innovative, but they demonstrated

a sobriety, unity of design and sophistication that completely

surprised the French public. The colour schemes were equally

unexpected: bright oranges, cobalt blue and brilliant greens—hues

virtually unknown in French decoration."

Back.

Stern, New York 1930, p. 338. Back.

"A Modern Decorator in New York," Architect and

Building News (November 26, 1926), pp. 632-34: "For

the inspiration of his decorative motifs, however, Mr. Reiss

has paid a good deal of attention to the work of the American

Indian and Aztec sculpture. Probably as a foreigner he surveys

the field of American inspirational sources with a fresh eye,

and, like one or two other artists, has been astonished at

the richness of Aztec art which can not only be considered

an indigenous but which contain boundless suggestions for

development ... Winold Reiss works in his New York studio

in conjunction with his brother, who is a sculptor, and who

shares enthusiasm for Mexican and Indian work. Both brothers

feel that native art has been neglected in favour of imported

details, and that in Indian work is revealed a sense of pattern

which is in itself an inspiration. Certainly some of the vermillion,

yellow and green interiors of the Crillon restaurants in New

York show a strong Indian suggestion." Back.

"Winold

Reiss - May 1913," typescript biographical sketch, Collection

of Tjark and Renate Reiss. Back.

Stem,

New York 1930, pp. 283-84: In 1920 Reiss had pioneered

a less scenographic restaurant design in New York at the Crillon

Restaurant at 15 East Forty-eighth Street, which he decorated

in what Edwin Avery Park described seven years later as a

"decidedly modern and thoroughly American taste, using

flat surfaces, broad and colorful painted decoration, based

on the patterns found in Navajo blankets and Indian pottery."

The zig-zag or chevron motif first appears commonly throughout

Reiss's designs for the interiors of the Alamac Hotel, insinuating

itself successfully into both his medieval and African themes.

After the middle twenties it occurs increasingly in the distinctive

advertisements for the Restaurant Crillon and later in those

for the Longchamps chain. (fig. 20). Back.

American

Architect (February 5, 1929), p. 173.

Back.

As

late as 1941 his earlier work on the Tavern Club led to a

commission from the architectural firm of Neville & Sharp

to design a new bar and dining room for Kansas City's Hotel

President. One of the architects wrote to Reiss, recalling:

"I remember having seen the murals you did for the Tavern

Club in the 333 Michigan Avenue Building in Chicago, some

years ago..," Neville & Sharp to Reiss, February

13, 1941, Collection of Tjark and Renate Reiss.

Back.

Charles

Collins, "Floreat Taberna! Temple of the Gay Heart and

the Quickened Mind," The Chicagoan (1928), pp.

11ff. Other contemporary accounts included: Athena Robbins,

"A Town Club Decorated in the Modern Style," Good

Furniture Magazine (March 1929), pp. 129ff.; "The

Tavern Club at 333 North Michigan Avenue, Chicago," The

Architectural Record (February 1929), pp. 163-66; "Decorating

the Modern Way," Restaurant Management (July 1929),

pp. 37ff.; The American Architect (January 5, 1929),

p. 36ff.; and "Art Moderne in Chicago's Tavern Club,"

National Hotel Review (April 27, 1929), pp. 62ff.

Back.

Stern, New York 1930, pp. 214-15: The 11,000-square-feet,

thirty-one-feet high ballroom, was reputedly the largest in

the United States, capable of holding more than 3,000 people.

Back.

OW. Wentz, "The St. George Goes Modern: In this largest

hotel of Greater New York are some fine examples of contemporary

decoration," The DuPont Magazine (1930), pp. 14-15.

Back.

Stern,

New York 1930, pp. 283-84: "After Prohibition's

repeal Reiss designed a white, blue, and black cocktail lounge

for the Crillon that was highly regarded by [Lewis] Mumford,

who found it conducive to drinking yet not 'so exciting that

you would get drunk at the first smell of a Martini'. Moreover,

the Crillon demonstrates what the more vital modern architects,

like Wright and Oud, always knew: that architecture designed

for our present style of living does not need to seek its

exponents and admirers among the color blind."

Back.

The

New York city chain grew from six locations in 1935 to at

least ten in 1946. Fred Brauen, "Winold Reiss,"

pp. 48-54, 70, has carefully detailed this evolution.

Back.

The

respected critic and historian Talbot Hamlin drew attention

to Reiss's achievements in the Longchamps restaurants in an

article entitled "Some Restaurants and Recent Shops"

in the widely read architectural periodical Pencil Points

(later Progressive Architecture) 20 (August 1939),

pp. 485-508. Hamlin described the problem of designing a modem

restaurant as a difficult one: "to provide the maximum

seating accommodation within a limited area, and also surround

the patrons with an atmosphere which will make them forget

the small amount of space they occupy and give them the illusion,

if not of privacy, at least of intimacy, in surroundings which

are gay and cheerful ... the idea is to furnish lots of color,

to break up the greater number of surfaces so as to produce

an agreeable sense of complexity, and to use mirrors to create

the illusion of increased size" concluding that the more

recent Longchamps, designed by Reiss, "have attained,

its seems to me, a remarkable success."

Back.

Except

for its beginnings in the M.A.C., it has been beyond

the scope of this analyis to present in any depth Reiss's

work in the area of graphic design. He contributed to a number

of leading American periodicals, including Scribner's

and Fortune, in addition to popular illustrations,

and was a fine printmaker. His most influential work, however,

was in interior design and packaging.

Back.

According

to Tjark Reiss, the Longchamps colors of vermilion, black,

and gold, used here, were the same as those in the silks designed

by Reiss for Henry Lustig's racing stable. Brauen, "Winold

Reiss," p. 48, repeats this. Back.

Vienna

1900, auction catalog, Sotheby's, London (September 23, 1993),

no. 53, ca. 1902. Back.

Stern,

New York 1930, p. 285. Back.

"le

plus chic, le plus luxueux, le plus original lounge de Montréal,"

Le Canada, December 29, 1949. Back.

Telephone

interview, February 1993, prompted by similarities observed

between Reiss's design for the Empire State Building Longchamps

(1938) and the interiors of Miami's Hotel Fontainebleau, designed

by Lapidus. Back.

|